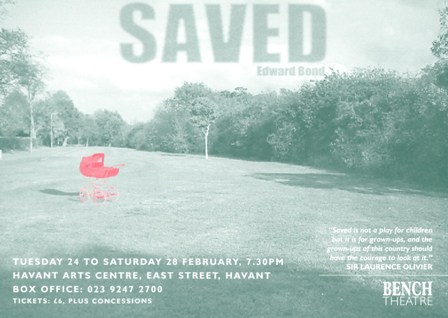

The Bench Production

This play was staged at Havant Arts Centre, East Street Havant - Bench Theatre's home since 1977.

Characters

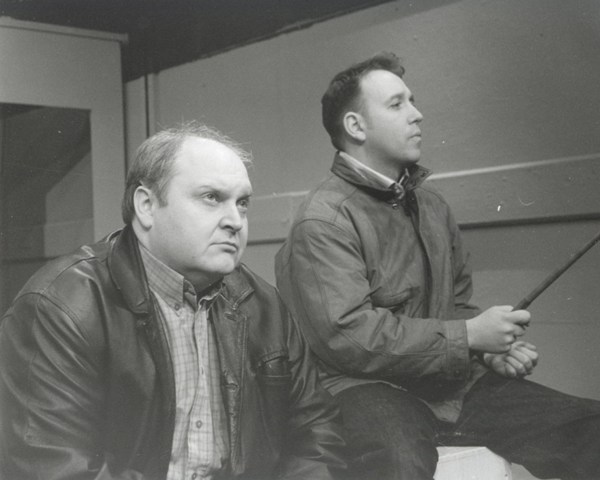

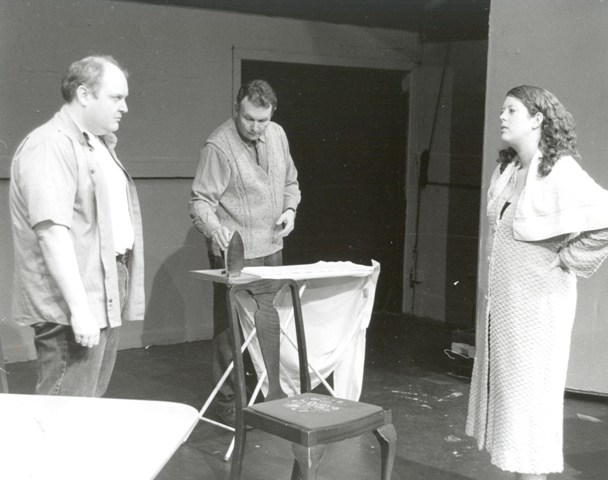

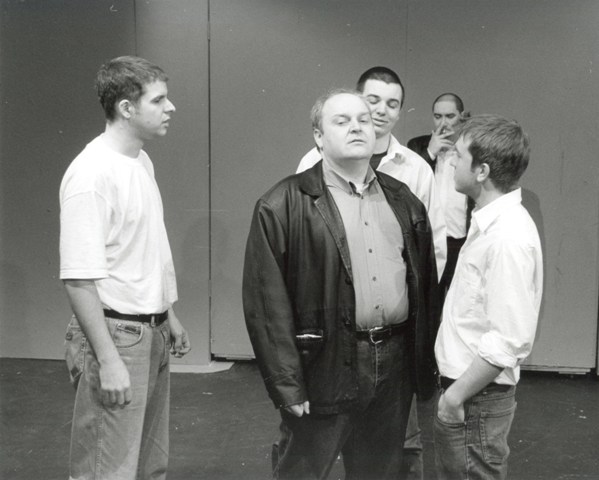

| Len | Mark Wakeman |

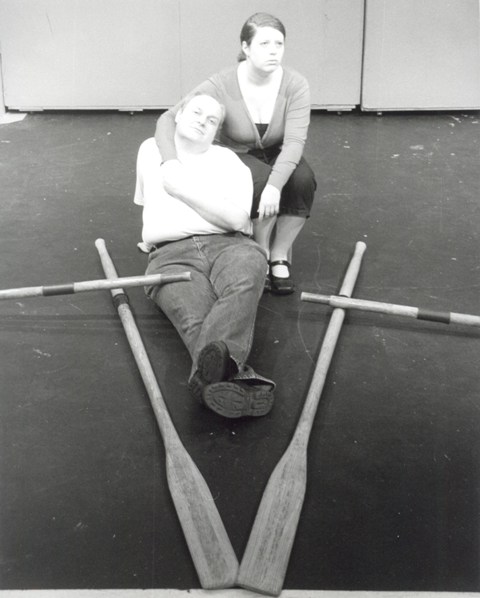

| Pam | Alice Corrigan |

| Mary | Nicola Scadding |

| Harry | David Penrose |

| Fred | Neil Kendall |

| Mike | Gareth Sandham |

| Pete | Damon Wakelin |

| Barry | Richard Le Moignan |

| Colin | Martin McBride |

| Liz | Vicky Hayter |

Crew

| Director | Nathan Chapman |

| Producers | Pete Woodward Sharman Callam |

| Stage Manager | Derek Callam |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Ann Gains |

| Costume Design | Michael Haigh |

| Poster and Programme Design | Nathan Chapman |

| Set Design | David Penrose |

| Sound Recordist | Darryl Wakelin |

| Front of House | Megan Utley |

Director's Notes

It is a very long process for me from first getting excited about a play and then pitching it to the membership, and the ideas I have on first reading of a play evolve and adapt over time and over rehearsals, especially as the actors bring so much to the play. It is almost a year since I first put down my thoughts about 'Saved', and was myself quite interested to see how much those initial thoughts had changed by now. So here, I suppose, is a "Before and After" of a director's brain, from first pitch to final production.

March 2003

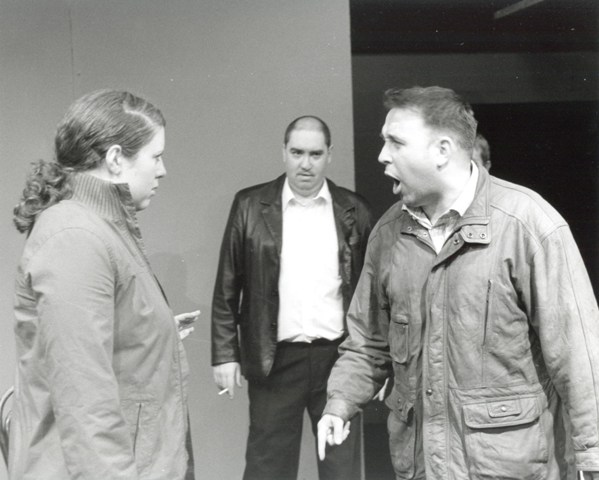

Central to the difficulties with the play are issues of morality. The majority of the characters seem to have no sense of right or wrong, no sense of respect for their fellow man, woman or child. This amorality is demonstrated in the play in a number of key scenes, through the bigoted dialogue of the lads, the seemingly complete absence of a maternal instinct in Pam, and most brutally of all, in the coup de theatre, which is the chillingly nonchalant slaughter of a baby in its pram. Despite this, the play itself is acutely moral, allowing the audience to affirm its own morality through the inevitable shock and disgust the play will provoke. A theme in the play is that goodness does survive, under any circumstances. The characters fight, joke, antagonise and self-destruct with no appreciation of consequence. Products of their economic poverty, this has now extended into a "poverty of culture" (New Statesman).

'Saved' gives us the opportunity to look back at a time still within living memory, compare it to our own, and ask the question "Have we really come as far as we like to think?"

Personally, the intense anger that I felt just on reading the play, while not entirely palatable, is such a humanity-reaffirming sensation that I think it should be made available to more people. It is nice to see a play that makes me laugh, makes me forget the miseries of the "real world," but sometimes, just sometimes, I want to see something that arouses such passions within me that I am shaking in my seat. The after-show drink becomes almost medicinal, rather than just luxurious!

February 2004

It is a tribute to the immense talent of Edward Bond that this play keeps on throwing up new ideas and information. At each rehearsal, for each scene, so many options were presented to us that we could have happily rehearsed for another three months and, at the end of it, still not have discovered everything that Saved has to offer.

It is a play of great subtlety and, in spite of the extreme acts that occur over its thirteen scenes, is understated in a typically British fashion. This is something of which Bond himself was acutely aware, and his contention that the death of a single child in a park is a "negligible atrocity" seems at first to be deliberately provocative. Unfortunately, nearly forty years after the play was first written, there have been far too many real-life instances of infanticide which have shocked, angered and outraged our collective sense of morality, and which are still fresh in our memory, and these cases may well cause us to view Saved with the same indignation and contempt as its original audience.

But to judge the play on the evidence of a single, albeit key scene is to fall prey to the reactionary tendencies of so much of the modern world. It is perhaps inevitable that the play will always be defined and condemned by its own depiction, but this takes away from the larger political and social arguments that I believe Bond is presenting. The death of the child is, indeed, a negligible atrocity, when compared to the state-sanctioned genocide of warfare, and Bond is keen to remind us of the fact by giving Mary and Harry a boy who was killed by a bomb in a park during the war. The anonymity of this child's murderers, and the sheer distance involved in committing the act make it much more sinister and unnecessary, particularly when governments, even in recent times, seem to talk about the deaths of civilians as though they are the eggs you have to break when making an omelette, as the saying goes.

But for me, the play became more about the people, not the politics. So often we are reminded that it is stories on a human level that appeal to us, it is the characters that we want to care about, more than the argument. So Saved started to work on a much more human level: it is a play about choices. The characters we see initially have no regard for the consequences of their actions and they suffer because of this. Tragically, there doesn't seem to be much of a learning curve for many of the characters, and they continue to make choices that are destructive to themselves or others, that don't offer positive solutions and seem to be selfishly motivated. It is out of this that Len emerges as the hero, although a flawed one. He is as guilty of rash decisions and actions as everyone else at first, but he makes a conscious choice to "do the right thing", regardless of how this will be perceived by others, despite the ingratitude of those whose lives he has an immediate impact on. It is important for me that Len is not seen as a weak character, a do-gooder who is taken for a ride. He may seem like a victim, easily manipulated, but he is, throughout the play, engaged in an enormous struggle to adhere to a moral code that has apparently been rejected by the rest of the world. To persevere in this way, to consistently do the opposite to what his upbringing, environment and culture might be telling him to do, smacks to me of great strength of character. I wouldn't call him a martyr as such, as I'm not sure he has completely grasped the cause he is fighting for, perhaps he is best described as a tainted saint.

Is Saved optimistic? Bond claims "almost irresponsibly" so. It has been a cause for some debate in rehearsal, and it is true that it is difficult to agree wholeheartedly, such is the understated nature of the play's climax and our modern hunger for unambiguous resolution. But I can see why Bond says the play becomes formally a comedy. People survive, sometimes only just, and the existence that the characters resign themselves to is far from ideal, but they do survive. Some of them are even making plans for the future, although whether these plans are to be seen through and even if they are moral remains to be seen. But we are left with the image of someone determined to make something better; Len may not have the necessary skills to do so, but it isn't going to stop him trying, just as it hasn't stopped him throughout the play. The question of optimism is probably one of the things that is hopefully to be discussed after the lights have gone down, and how people come away from this play feeling is very much dependent on the individual's personal standpoint.

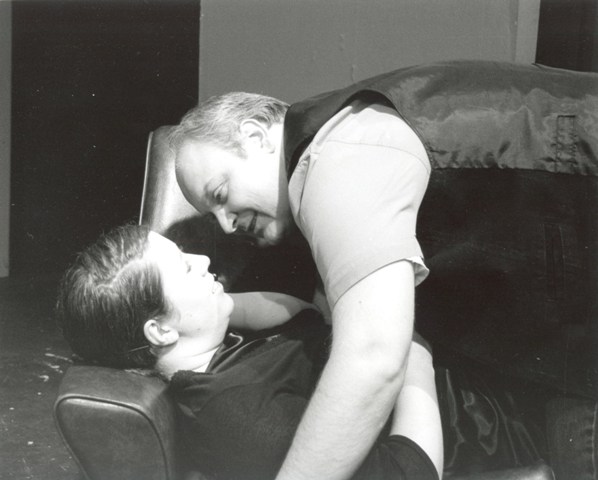

What has been pleasing and, perhaps, surprising to discover is how much humour resides in the play. The laughter comes from unexpected quarters and at unexpected times, in the least likely of situations. The comedy ranges from coarse jokes and sexual innuendo, through Ealing-esque slapstick and friendly banter. At times it is ironic, you may find yourself laughing at the characters rather than with them, and you may find yourself laughing simply because that is the only thing left to do - the quintessentially English attitude of "You've got to laugh, otherwise you'll cry." A lot of attention has been paid to the variety of tone in the play, the acutely observed language, the complexity of the characters.

It has been a richly rewarding experience to work on this play. It is difficult, poses many problems both aesthetic and ideological, and asks many questions of the cast and crew. At every turn it has borne scrutiny, surprised me, terrified me and left me in awe. I sincerely hope it will do the same for you. And if this company has come even close to doing justice to one of the greatest plays of the twentieth century, there is nothing more that I could hope for.

Nathan Chapman

Reviews

The NewsMike Allen

Production entertains but it's a play I don't like much

Being voted the 20th century's 11th most 'significant' play in the English language does not make Saved the 11th 'best'. It is too loosely constructed for that. But Edward Bond's play is significant in having offered, in 1965, a newly graphic portrayal of the savagery endemic in a social underclass. And its depiction of a careless attitude to killing still resonates today. So the fact that I don't much like the piece is perhaps irrelevant - because I am not sure we are meant to like it.

The characters, after all, are not generally endearing, although the relationships do have some subtle shades of grey and there are plenty of laughs. But Nathan Chapman's Bench Theatre production is highly commendable.

Mark Wakeman as Len and David Penrose as the mostly silent Harry do their best to present human faces to a harsh world. The incomparable Penrose sits centre-stage, pursing and unpursing his lips, looking this way and that, commanding attention without scene-stealing. These characters at least show signs of finally trying to get on positively with their lives, persuading Bond to say his play was "almost irresponsibly optimistic". Hm. Admirable performances also come from Alice Corrigan, Nicola Scadding, Damon Wakelin and particularly Neil Kendall as Fred. He ranges with frightening ease from laddish charm to explosive rage.

The News, 25th February 2004