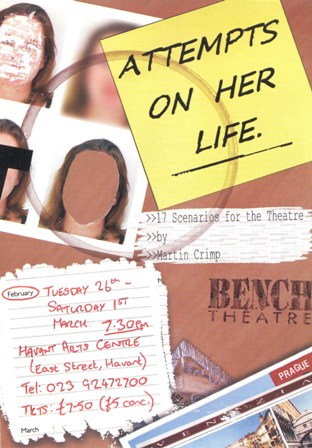

The Bench Production

This play was staged at Havant Arts Centre, East Street Havant - Bench Theatre's home since 1977.

Cast

| Jeff Bone |

| Zoë Chapman |

| Sue Dawes |

| Emilie Ekstrom |

| Sarah Fencott |

| Hadleigh Harrison |

| Neil Kendall |

| Barbara Netherwood |

| Callum West |

| Julie Wood |

Crew

| Director | Nathan Chapman |

| Producer | Robin Hall |

| Stage Manager | Peter Corrigan |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Sharman Callam Elizabeth Lewin-Diani |

| Lighting Design | Jacquie Penrose |

| Lighting Operation | Lucy Tipper |

| Sound Recordist | Darryl Wakelin |

| Sound Operation | Emily Tipper |

| Video Consultant | Darryl Wakelin |

| Technical and Special Effects | Peter Corrigan |

| Set Construction | John Wilcox |

| Photographs | Dan Finch |

Director's Notes

The term "director" for this production must be used loosely. In fact I feel fraudulent in adopting this title, as this project has been, and was always intended to be, a highly collaborative one, in which the divisions between actors, director, crew and designers are blurred by everyone having responsibility for making the creative and interpretative decisions about the performance.

Normally a director has a strong sense of what they want to say about their play before the first rehearsal, and the work with the actors involves blocking out the movement on stage, ensuring characters are believable and consistent, and providing the actors with information about how you are interpreting the play, in other words what themes and ideas already inherent in the writing, you are trying to emphasise through the staging.

For Attempts on Her Life, however, the approach was different. On the page, Crimp's play is an amorphous, ambiguous and troublesome beast, at the same time open to interpretation and unforgiving in its precision. The fundamentals of 'normal' plays - plot and characters, are absent, and all you have is a few arrangements of dialogue, with the only impositions being when this dialogue is spoken by a new voice, and the occasional request for using other languages. Hence, an awful lot of groundwork has to be done before you can even start to 'rehearse' the play.

So, how does a company tackle such a text? The answer is with a great deal of trepidation, open-mindedness and flexibility. When the cast gathered for the first read-through, I warned them that my answer to most questions was likely to be "I don't know." I wanted the true answers to come out of an exploration of the text, to respond to what we had and expand on this through the various experiences of a diverse ensemble. Our version of this play was going to be defined by the people involved with it, rather than by a single, directorial intent.

Exploration

Our first task was to gather around a table and read the play. We divided the dialogue quite randomly between the actors, and read through each of the seventeen scenes, after each episode discussing what we thought the text was indicating, in terms of characters, context or meaning. Some decisions seemed to be arrived at arbitrarily: "This scene sounds like it has three voices," for example, or "I think this speech suits a male speaker." We gathered pages of notes on possible contexts for the play, rejecting nothing, putting everything into the mix for further experimentation.

In the recent National Theatre revival, Martin Crimp allowed Katie Mitchell to cut Scene 1, All Messages Deleted, and the text now permits this edit in all productions. But it seemed to me that the answer-phone messages in this scene serve as an introduction to the rest of the play. Phrases that we hear in this episode recur throughout the play, and I felt it was a useful way in to the play. The messages introduced us to a number of characters we were yet to meet, and so I opted not only to retain this scene, but to use it as the spring board for developing our production.

Fortuitously, we had ten actors, and there are ten different people leaving messages, Giving each actor one message, we tried a couple of improvisations. First each actor was to respond as though the message was left for them, and second they were to act as the character who leaves the message. The results were compelling and varied, but each emerging character seemed to contribute to a coherent sense of who Anne was and what has happened to her. This mysterious, unseen woman became someone who has gone missing after getting involved in all manner of dangerous or immoral activities, including prostitution, terrorism, fencing stolen goods, but also a woman who started out with philanthropic intent.

We developed this work by having each actor bring in an object that had some personal significance to them. The instruction was that this object belonged, in fact, to Anne, and each actor has to explain how it came in to their possession and what memories it triggered about their relationship with Anne. Again the results were fascinating, ranging from fleeting encounters to full-blown friendships and sexual relations. We started to see a history emerging, and not only did we begin to understand who Anne was, but also who these other people in her life were. Now we had the characters and back story, it was time to turn our attention to the text once again.

Finding the forms

I didn't want the actors to be restricted by these newly discovered characters at the expense of other ideas, so we didn't refer directly to these initial exercises when working on the text. Rather the focus was on identifying a solid, workable context for each scene. The media pervades the entire play, and what emerged was a sense that each scene depicted some kind of outside agency creating, manipulating or responding to an image of Anne, thus we ended up with film executives, PR teams, photographers, journalists and audiences, and each context dictated the form of the scene. We have tried to vary each episode, really out of necessity, as it is impossible to reach a unified definition of Anne because the play is full of contradictory accounts. It seemed for a long time that our initial exploration was to have little influence on the finished product, but there were certain moments in rehearsal when, as if by magic, we found ourselves remembering those early characters and realising that they were consistent with the roles people were playing in various scenes. I loved these moments - they vindicated the exploratory process and made us realise that everything we have tried has had an influence on the shape of the play, even if only on a subconscious level.

I mentioned flexibility and this became a crucial attribute as actors found themselves being given totally new lines, or being placed in scenes they were not in to start with. In some cases we scrapped entire scenes are started again. As I write this, a mere seven days before the first night, I am planning to overhaul two key scenes as we discover that they don't seem to be working as they should. The set design has also changed, affecting the blocking of the play, and for this reason the cast has had to respond rapidly to these changes. Despite these alterations, I am now confident that the production has gained some coherence, and rather than being a formless lump, it has evolved into a varied theatrical experience.

So what's it all about?

It would be tempting to go down the road of "letting the audience decide what the play means" but this strikes me as a poor disguise for a lack of investigation. I am happy to say that all those "I don't knows" have been replaced by a clear sense of what Attempts on Her Life means. This conclusion has been reached not by our own impositions on it, rather by our instinctive responses to it, and by input from other, at times unlikely, sources.

I was re-reading the script a few weeks ago and noticed a quote from Jean Baudrillard that Crimp has used to preface the text of his play: "No-one will have directly experienced the actual cause of such happenings, but everyone will have received an image of them." The significance of this hitherto disregarded quote became apparent to me, as did the fact that, for all his posturings that this play has no specific meaning and is in some cases writing for the sake of it, Crimp very clearly knew what he was saying. As I started to reflect on our work on the play, it seemed as though our organic interpretation of the scenes was sympathetic to this notion.Baudrillard seems to be saying that, in our media-saturated world, we have access to a staggering amount of information about people and events of which we haven't had first hand experience. Yet at the same time these people and events touch our lives, stay with us, and we form opinions about them while simultaneously allowing them to influence our outlook in other aspects of our lives.

So what we have, with 'Attempts on Her Life', is a number of attempts to define an individual, Anne, by people who have never known her, yet have a lot of information about her. Our production, whether by accident or design, extends this concept, and what we see is the construction of an identity for public consumption. The main perpetrators in our version would seem to be the pair of film executives pitching their ideas to each other in the second scene, yet their lead is followed by all manner of agencies engaged with piecing together what information they have. And where things don't fit, or they contradict each other, these agencies embellish with details that suit their own agendas. In a bizarre case of art mirroring art, the process you will see the characters engaging in tonight is exactly the same process that our ensemble has gone through over the last three or four months. If, during the course of the performance, you find yourself forming opinions, reaching conclusions about who Anne is only to be forced into re-evaluating these decisions a few minutes later as new details come to light, that is exactly what we have done at every rehearsal.

So whilst 'Attempts on her Life' has been criticised in the past for being pretentious, cold soulless, it seems to me that at its core is a very fundamental idea - the elusive nature of human identity, the struggle to define an individual despite knowing it is impossible to do so. We all have moments where we question who we are and try to find answers in other people, and there is nothing more human that a play could explore than this quest to make sense of our own existence and place in this world.

I have been privileged to work with so many talented, enthusiastic people in bringing this challenging play to the stage. The cast, the stage managers, producers and designers have applied themselves with such dedication and tolerated my frequent moving of goalposts with good humour. I haven't enough words to express my gratitude and admiration for them all. And thanks, not least to you for stepping into the unknown with us this evening. I hope you will be rewarded by an intriguing, varied, challenging yet entertaining piece of theatre.

New Tricks - The place of new technology in 'Attempts on Her Life'

There is an ongoing debate about the use of new technology in the theatre. What is accurate is to say that incorporating film, projections and other "non-theatrical" techniques into performances seems to be increasing in popularity, and it is the professional theatre that leads the way. At first glance, this might seem logical. Film is perceived as a time-consuming, expensive pursuit that can only be considered by companies with the time, the resources and the professional expertise to make it work, yet in many respects film is a perfect tool for amateur theatre.

Why? Amateur companies tend to have much shorter runs, in smaller spaces and with much less time in which to construct and road-test elaborate sets, making physical construction very ineffective in terms of time and cost. But film lends almost infinite flexibility to a production. The audience can be transported to the four corners of the globe in an instant through the projection of simple, recognisable images. The visible space can be distorted, meaning entirely separate locations can concurrently occupy the same space as the performers, and the apparent limitations of what can take place in real time on stage are removed with the careful use of pre-recorded and edited footage. And all of these things are extremely portable, particularly in this digital age.

With a play like 'Attempts on Her Life', it is impossible to ignore the pervasive influence the broadcast media have had on the writer, and as this theme leapt out at me from the very beginning, it was always a question of how we will use new technology, rather than if. We have been very lucky to know a number of people whose knowledge in this field has allowed us to push the boundaries of what even I thought would be possible for a company like Bench, but I would be keen to stress that it hasn't been a case of playing around with a new toy. The application of film and digital media has been carefully thought out, and I would say that the decisions have been made according to a couple of golden rules:

- There must be a reason for using these devices.

Not just in terms of aesthetics, but also thematically. The media is a central presence in the play, and therefore our conspicuous cameras and projectors as well as what they produce are directly related to the ideas in the text. There is a point to what is being said on the stage by having these things. If they were irrelevant, they wouldn't be there. - Film must never replace theatre.

'Attempts on Her Life' is theatrical event, and therefore the audience's experience must remain a theatrical one. It has been a key consideration that the projections should never be used to do what theatre can do perfectly well on its own. The function of film has been to focus the audience's attention to something specific on the stage, to add another dimension to the action, to support the live work of the actors and perhaps to subvert it at times, but never to replace it.

Finally, 'Attempts on Her Life' is a very modern play, and the use of these elements gives our production a similarly modern feel. I believe that we have been true to the spirit of Crimp's play, and have acquired new skills, explored further possibilities in the process. Does what we have done here reinforce the positives that new technology can bring to the theatre? Or does this technology simply get in the way? Ultimately, that is for you, the audience to decide, and I would be delighted if these decisions provoke the same diversity of views that 'Attempts on her Life' as a play seems to encourage.

Nathan Chapman

Reviews

The NewsJames George

Bench puts its mark down on fascinating human exploration

Modern theatre comes in many forms and in the greater Portsmouth area we are very lucky to have local companies that are prepared to tackle newer, lesser-known, performance pieces. The Bench theatre company has chosen to present Martin Crimp's Attempts On Her Life which is not so much a play as a theatrical experience. There is no story, only a situation. Anne, the invisible focus of the piece, has disappeared. She - her personality, her life - is defined by the words and actions of people who do not know her. And that's it.

The programme notes, somewhat defensively one feels, leap to rebuff allegations of pretentiousness and there's no doubt that some quarters would raise this point against the piece - but regardless of the truth of that it remains a fascinating exploration of human individuality, nevertheless.

Director Nathan Chapman's cast aren't always successful in their handling of the complex dialogue. Jeff Bone and Hadleigh Harrison's first scene suffered from an overabundance of pace to the detriment of clarity, but both of these actors later got the measure of the dialogue; some voices - a critically important piece of this show - were drowned out by music.

Neil Kendall is impressive in his scenes - particularly the brilliant scene comparing Anne to a car - and Callum West's contributions showed flashes of real skill. Zoë Chapman stood out among the women. It's good to see theatre like this being presented locally and the Bench's opening night audience was a fair size. This is theatre for the thinking man or woman. Enjoy. The play continues its run until Saturday.

The News, 27th February 2008